The impact of power structure imbalances

Gender-based violence is more than being punched in the face. Other forms of violence against women include hate speech, stalking and sexual harassment. The various manifestations of physical, psychological and sexual violence are the product of power structure imbalances that manifest themselves both on the level of society and in private relationships. It is therefore primarily women who are affected by the different forms of gender-based violence. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified violence as one of the largest health risks that women face.

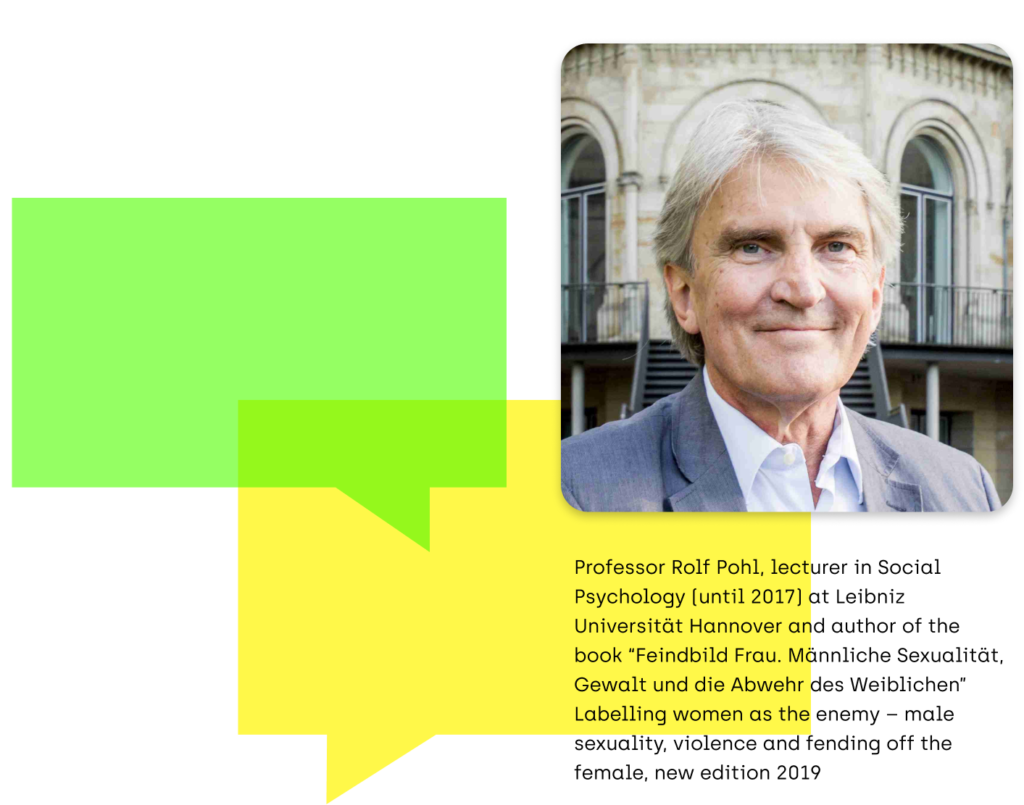

Interview with Professor Rolf Pohl

In an interview with sociologist and psychologist Professor Rolf Pohl, we discuss the root causes of virtual and actual violence against women.

Violence against women is often played down in the media as “family drama” and thereby relegated to the private sphere, without raising the question of what its social causes could be. How is the phenomenon of violence against women embedded in the overall context of social power structures?

Despite everything that has been achieved on gender policy, we haven’t made nearly as much progress towards gender equality as we are made to believe. Often, we hear indignation expressed about how it’s high time to put an end to measures favouring women, supposedly male-hating feminism and, more generally, all that “gender nonsense”. What these voices leave out and deny is that we still live in a hierarchical system of gender asymmetry, in which the male is dominant. Sociologist Sylka Scholz describes the status quo as “mentally and morally dominant systems of values and classification” that imply a cultural hierarchy of binary sexuality and that, at their core, are founded on the principle of “the male being both the norm and superior to the female” – whereas the female remains subordinate and is both less important and less valuable.

This system of male dominance is a cultural phenomenon deeply engrained in the perceptual and belief patterns of the individual. The many variations of antifeminism that keep re-emerging, our society’s undiminished and widespread everyday sexism and, above all, the persistently high levels of violence against women in all its forms are proof of how entrenched these asymmetrical gender relationships are, along with the latent gender norms that accompany them. Against this background, for example, it is scandalous when the police, the judiciary and many media outlets refer to the killing of women by their partners or ex-partners in a de‑gendered way, with terms such as “relationship-related crimes”, “family dramas” or “partnership-related conflicts” – instead of speaking of femicides that are motivated by a deep hatred of women.

We still live

in a hierarchical system of gender asymmetry, in which the male is dominant.

Violence against women, girls and non-binary people is one of the most widespread forms of violence globally. How does violence against these groups manifest itself?

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines direct, external violence as the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against another person that results in, or has a high likelihood of resulting in, psychological harm, bodily injury or even death.

According to this definition, the gender-based violence that is addressed here includes actual and virtual bullying, lewd comments, obscene jokes, unwanted touching, grabbing, sexual advances and other forms of harassment, sexual and sexualised violence, ranging all the way to destructive attacks in the form of rape and, ultimately, the intention to eliminate the woman as an independent subject – by killing her. The boundaries between these various forms of violence are fluid rather than rigid.

A circle of violence

Rather than simply arising out of the underlying hierarchy of the sexes, violence against women actually confirms these stereotypes. It thereby solidifies precisely the structures from which it originated in the first place. Gender-based violence has far-reaching effects; it not only harms the affected women and girls themselves, but also impacts their families and society in general. Moreover, violence is often passed down from generation to generation.

In your view, what role do online hate speech and digital violence against women play in this canon of violence?

The internet acts as a catalyst for the rapid spread of misogyny. It provides a space that is both open and largely “protected”, in which users are free to express and exchange with like-minded individuals their hateful views about women’s bodies and women’s supposedly “treacherous” nature. In terms of group psychology, this creates and fosters a feeling of importance, significance and cohesion, through clearly defined and shared stereotypes and prejudices, a common enemy. The exchange of hatred in a virtual space is a necessary prerequisite for, and catalyst affiliated with, actual violence. This can be observed across the board, from pick-up artists and Incel online discussion fora to the well-known right-wing terrorists who carried out attacks in Oslo/Utoya, Christchurch, Halle, Hanau, etc. The anti-feminism and misogyny of all these perpetrators cannot be explained without the radicalisation they underwent in the respective internet fora and image boards.

The reflex to invert the perpetrator-victim relationship always serves to deflect blame and responsibility.

Who are the main actors with regard to online violence against women? What networks do they have?

These platforms are loosely affiliated, masculinist (male-rights-focused), anti-feminist, conspiracy-theory and right-wing-extremist websites, catering to groups and ideologies that overlap to some extent. This once again shows how much right-wing schools of thought and misogyny go hand in hand. That said, except for some small wannabe leaders, these loosely affiliated networks have no obvious main actors as seen in traditional mass movements, and neither is there any clear-cut organisational structure.

And yet they do exhibit some of the classic traits of mass psychology, albeit in modern guise: first, the members of a mass movement or group do not necessarily need to assemble in the real world; masses can gather virtually, too. Second, they do not always need a leader to whom followers swear allegiance. Such a bond can also be formed through a shared ideology or a common worldview. And, third, extremely negative emotions, especially hatred, can create this strong feeling of group cohesion. All three of these preconditions are met in the case we are talking about here.

The tip of the iceberg

A study of the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth that was published in 2020 found that every third woman in Germany was affected by physical and/or gender-based violence at least once in her lifetime, and that approximately one woman in four becomes the victim of physical or sexual violence perpetrated by her current or former partner. Effectively countering violence against women requires tackling the structures and preconditions that enable such violence. These are largely still a blind spot in the debate on gender-based violence. In this respect, violence against women is merely the tip of the iceberg – the most extreme and visible manifestation of the patriarchy that runs through all structures of our society.

To what extent is there a link between violence against women and (problematic) concepts of masculinity?

This link is a fundamental characteristic of our gender order. In male-dominated societies, men are still more or less under pressure to emphasise not only how they differ from women, but especially how they are superior to them; they are under pressure to “demonstrate” that they are the “more important” sex and to prove this in cases they deem an “emergency”. It must be said that this feeling of male superiority is based on a subconscious degradation and devaluation of women. And yet in the domain of sexuality, men are (supposedly) placed under the control of an “outside actor”, namely women. Thus, the desire for autonomy and superiority turns out to be a deceptive illusion. Against this background, masculinity is a fragile state susceptible to risk. When conflicts do arise – which are then always felt to be a crisis of masculinity – they “must be” repaired; if need be, through violence. And this is, psychologically speaking, one of the most significant causes of violence against women.

Masculinity is a fragile state susceptible to risk. When conflicts do arise – which are then always felt to be a crisis of masculinity – they “must be” repaired; if need be, through violence.

What can be done about “victim blaming” – that is, the problem that women who report sexual assault or have experienced violence are often not believed, or in some way considered to be “complicit”?

What is needed here is a fundamental change of mindsets, so that we can break the current cycle of machismo and buddy networks. The reflex to invert the perpetrator-victim relationship always serves to deflect blame and responsibility. When this reasoning is expressed by one’s own partner, or by the police officers, lawyers and journalists who are involved in a case, then one of the aims is always to eschew personal responsibility. This means that clear signals need to be sent, not only in each specific case but also in general, that victim blaming is an expression in all those involved of the very same ambivalent and malicious attitude towards women as that of the perpetrator, accompanied by the very same, typical defence mechanism to save and reaffirm their masculinity.

13 %

According to a study published in 2009, approximately 8000 rape charges are filed in Germany each year. In only a little over 1000 of these cases do such charges lead to a judgment being passed down – a conviction rate of 13%. This low number of convictions may be one of the many reasons why so few women even report sexual assaults or bodily harm. It must therefore be assumed that, for every instance of rape that is reported, many more go unreported.

It is part of the phenomenon of violence against women that victims often have a hard time confiding in others or looking for help. This is especially true if they are in a relationship with the perpetrator. Why do victims find it so hard to go get help? What can be done to make it easier for them?

As a man, it feels slightly presumptuous for me to answer that question. But I do want to cautiously suggest one thing: there are a number of known reasons why women who become victims of violence do not, or rarely, talk about such acts, get help, or file a police report. Shame is often mentioned, and this to some extent shows how much the victim has adopted the male perpetrator’s reasoning that he acted in self-defence, wondering if she “might not be herself to blame”. What is especially important, however, is the well-known and constantly reaffirmed solidarity among males, which tends to invert the perpetrator-victim relationship. The woman’s fear of losing her dignity and being made a victim all over again must be properly understood, accepted and put to use for effective countermeasures to be taken. In principle, however, this will be impossible, or at least difficult, as long as the more deeply rooted structures of hierarchical gender order remain unchallenged.

Further information

There are many places where the victims of physical, psychological and sexual violence can find help. At the initiative of the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth, a website has been set up that provides access to numerous points of contact throughout Germany that can provide help and advice.

We want to encourage all those affected to seek support. Furthermore, we appeal to everyone’s civic duty and ask those who are not themselves affected to help and support those who need it.

@zeichensetzen.jetzt

@zeichensetzen.jetzt